Posts

- How many servers before it's worth it? Configuration management really kicks in to its own when you have dozens of servers, but how few are too few to be worth the hassle? It's a tough one. Nowadays I'd say if you have only one server it's still worth it - just - since one server really means three, right? The one you're running, the VM on your laptop that you're messing around with for the next big software upgrade, and the next one you haven't installed yet. If you're running a server with anything remotely important on it, then having some chef-scripts to get a replacement up and running if the first goes up in smoke is a really good time-critical aid when you need it most.

- How do you get started with chef? Well, it's tough, the learning curve is like a cliff. Chef setups have three main parts - the server(s) you're setting up (the "node"), the machine you're pressing keys on (the "workstation") and the confusingly-named "chef server" which is where "nodes" grab their scripts ("cookbooks") from. It makes sense to cut down the learning, so I'd recommend using the free 5-node trial of their Hosted Chef offering. That way you only need to concentrate on the nodes and workstation setup at first - and when you run out of nodes, there's always the open-source chef-server if the platform is too expensive.

- Which recipes should I use? There are loads available on github, and there's links all over the chef website. In general, I recommend avoiding them, at least at first. Like I mentioned, the learning curve is cliff-like and while you can do super-complex whizz-bang stuff with chef, the public recipes are almost all vastly overcomplicated, and more importantly, hard to learn from. Start out writing your own - mine were little more than a list of packages to install at first. Then I started adding in some templates, a few scripts resources here and there, and built up from there as I learned new features. Make sure your chef repository is in git, and that you're committing your cookbook changes as you go along

- Where's the documentation? I'd recommend following the tutorial to get things all set up, while trying not to worry too much about the details. Then start writing recipes. For that, the resources page on the wiki tells you everything you need to know - start with the package resource, then the template resource, then on to the rest. There's a whole bunch of stuff that you won't need for a long time - attributes, tags, searches - so don't try learning everything in one go.

Getting Involved in the Operations Working Group

For the last few years I've been trying to get more people involved in the Operations Working Group - the team within the OpenStreetMap Foundation that runs all of our services. Each time I think "why aren't more people involved", I try to figure out some plausible barriers to entry, and then work on fixing them.

One of the reasons is that we're very quiet about what we do - there's a pride in keeping OpenStreetMap humming along and not causing too much of a fuss. But the lack of publicity hurts us when we're trying to get more people involved. Hence this blog post, among other reasons.

I've been working recently (as in, for the last few years) on making as much of our OWG activities public as possible, rather than hidden away on our mailing list or in our meetings. So we now have a public issue tracker showing our tasks, and we also publish a monthly summary of our activities.

To make OpenStreetMap work, we run a surprisingly large number of servers. For many years we maintained a list of our hardware and what each server was being used for on the OpenStreetMap wiki, which helped new people find out how everything works. Maintaining this information was a lot of work and the wiki was often outdated. For my own projects I use Jekyll to create static websites (which are easier to find hosting for than websites that need databases), and information on Jekyll sites can be generated with the help of data files. Since OWG uses Chef to configure all of our servers, and Chef knows both the hardware configuration and also what the machines are used for, the idea came that we could automate these server information pages entirely. That website is now live on hardware.openstreetmap.org so we have a public, accurate and timely list of all of our hardware and the services running on it.

Now my attention has moved to our Chef configuration. Although the configuration has been public for years, currently the barrier to entry is substantial. One straightforward (but surprisingly time-consuming) improvement was to simply write a README for each cookbook - 77 in all. I finished that project last week.

Unless you have administrator rights to OSMF hardware (and even I don't have that!) you need to write the chef configuration 'blind' - that is, you can propose a change but you can't realistically test that it works before you make a pull request. That makes proposing changes close to impossible, so it's not surprising that few non-administrators have ever contributed changes. I have experience with a few tools that can help, the most important being test-kitchen. This allows a developer to locally check that their changes work, and have the desired effect, before making a pull request, and also it allows the administrators to check that the PR works before deploying the updated cookbook. Both Matt and I have been working on this recently, and today I proposed a basic test-kitchen configuration.

This will only be the start of a long process, since eventually most of those 77 cookbooks will need test-kitchen configurations. Even in my initial attempts to test the serverinfo cookbook (that generates hardware.openstreetmap.org) I found a bunch of problems, some of which I haven't yet figured out how to work around. There will be many more of these niggles found, but the goal is to allow future developers to improve each cookbook using only their own laptops.

All of these are small steps on the long path to getting more people involved in the Operations Working Group. If you're interested in helping, get stuck in to both our task list and our chef repo, and let me know when you get stuck.

This post was posted on 28 July 2016 and tagged chef, development, OpenStreetMapCoding and writing with the Atom editor

Atom brands itself as "A hackable text editor for the 21st Century". I first used Atom in August 2014 as an alternative to the Kate editor that comes with Ubuntu and which I had used for many years before that. I was drawn towards Atom by all the publicity around it on Hacker News, and it seemed to have momentum and a few useful features that Kate was lacking. It didn't take me long to find myself using Atom exclusively.

Much is said online about Atom being slow to respond to key presses, or that it's built in JavaScript, or that it uses a Webview component to render everything, or some other deeply technical topic, but none of those topics are worth discussing here.

Instead, a key feature for me is that Atom is built on an extensive a plugin architecture, and ships with a bunch of useful plugins by default. There are hundreds more available to download, but trawling through the list is a pain and there's always a few gems buried in the long tail. To save you some hassle, here's a list of the plugins that I use. I've divided them by the three main tasks for which I use Atom regularly - cartography, coding and writing.

Cartography

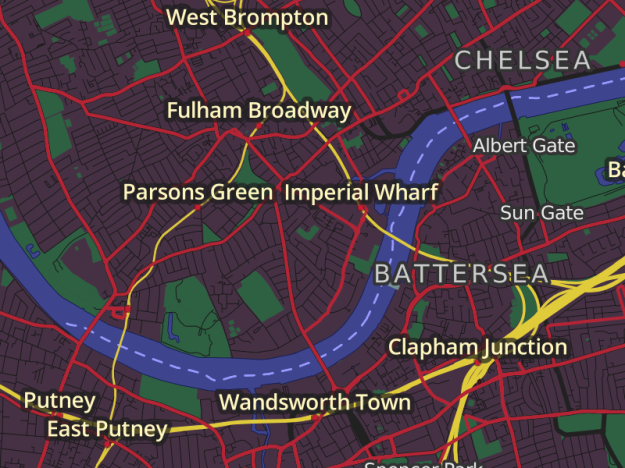

language-carto - "Carto language highlight in Atom". I only found out about this recently from Seth but, as you can imagine, it's very useful when writing CartoCSS styles! Finding out about this plugin by chance conversation is what sparked the idea of writing this post.

color-picker - "A Color Picker for Atom". I use Atom to edit all my CartoCSS projects, so this seems like a good idea, but I haven't actually used it much since installing. I prefer Inkscape's HSL colour picker tab when I'm doing cartography, and working in Inkscape lets me quickly mock up different features together to see if the colours balance.

pigments - "A package to display colors in project and files". This simply highlights colour definitions like #ab134f with the appropriate colour - almost trivial, but actually very useful when looking at long lists of colour definitions.

Development

git-blame - "Toggle git-blame annotations in the gutter of atom editor". I only started using this last week and it's a bit rough around the edges, but it's quicker to run git-blame within my editor than either running it in the terminal or clicking around on Bitbucket and Github. Linking from the blame annotations to the online diffs is a nice touch.

language-haml - "HAML package for Atom". I was first introduced to HAML when working on Cyclescape and instantly preferred it to ERB, so all my own Ruby on Rails applications use HAML too. This plugin adds syntax highlighing to Atom for HAML files.

linter - "A Base Linter with Cow Powers", linter-rubocop - "Lint Ruby on the fly, using rubocop", and linter-haml - "Atom linter plugin for HAML, using haml-lint". I'm a big fan of linters, especially rubocop - there's a separate blog post on this topic in the works. These three plugins allow me to see the warnings in Atom as I'm typing the code, rather than waiting until I save and I remember to run the tool separately. Unfortunately it means I get very easily distracted when contributing to projects that have outstanding rubocop warnings!

project-manager - "Project Manager for easy access and switching between projects in Atom". I used this for a while but I found it a bit clunky. Since I'm bound to have a terminal open, I find it quicker to navigate to the project directory and launch atom from there, instead of clicking around through user interfaces.

Writing

Zen - "distraction free writing". This is great when I'm writing prose, rather than code. Almost all my writing now is in Markdown (mainly for Jekyll sites, again, a topic for another post) and Atom comes with effective markdown syntax highlighting built-in. I'm using this plugin to help draft this post!

That's it! Perhaps you've now found an Atom plugin that you didn't know existed, or been inspired to download Atom and try it out. If you have any suggestions for plugins that I might find useful, please let me know!

This post was posted on 23 March 2016 and tagged cartography, development, toolsOpenStreetMap as Global Infrastructure

Shortly after the SotM US Conference in New York last year I was at a café discussing the future of OpenStreetMap. I was trying to describe my thoughts on how OSM could be perceived in a few years time and coined the phrase "Global Infrastructure" to label my thoughts.

So what do I mean by Global Infrastructure? I was thinking that over the next 5-10 years (bearing in mind OSM is already over 10 years old) that it would no longer be thought of as an interesting open source or open data "project". It would no longer be something cool or unusual that you find out about, it'll just be something that exists, that permeates the world and that people and organisations all over the globe will be using and depending on OpenStreetMap without much further thought. Like the PSTN - the global system of telephone networks that means you can call anyone else on the planet - OSM will become Global Infrastructure that powers millions of maps.

We're already at the stage where OSM is a routine and necessary part of the world. There are hundreds of non-tech organisations using OpenStreetMap every day, from the World Bank to local advocacy groups. I could try to make a list but I'd be here all day and I'd miss hundreds that I don't even know about. It's been at least five years since the various interesting uses and users of OpenStreetMap become much bigger than my own knowledge horizon! And this list of users will continue to grow and grow until the absence of OpenStreetMap will become inconceivable.

So beyond a catchy label, what does the concept of Global Infrastructure mean in practice? Well, if nothing else, I use it to guide my thoughts for the OSMF Operations Working Group. We're being depended on, and no longer by a few thousand hobbyists who can tolerate some rough edges here and there. We're going to have to keep building and scaling the core OSM services, and yet at the same time fade into the background. In a couple of years, if not already, most people in the OpenStreetMap community won't even consider how it all works.

There's a never-ending series of technical challenges that the Operations team faces, some of which I can't help with directly. So instead I'm keeping my focus on scaling our team's activities, whether that's automating our server information pages, systemising our capacity planning, publicising our activities or lowering the barriers to getting more people involved in the work that we do.

2016 will also see us working on new approaches to running our infrastructure. Perhaps not many visible changes, but improved systems for internal event log management and adapting various services to use scalable object storage are two projects that are high on my list - as are the perennial tasks around scaling and ensuring availability of the core database.

The challenge of moving OpenStreetMap beyond being "just a project" and into "Global Infrastructure" goes much wider than the work of the OWG. It will affect every part of the project, from our documentation to our communications to how we self-organise tens of thousands of new contributors. I hope we can set aside anything that we no longer need, keep up our momentum, and seize the opportunities to build on what we have already achieved.

This post was posted on 11 January 2016 and tagged OpenStreetMapSome OpenStreetMap Futures

Earlier this year I was invited to give two presentations at the State of the Map US 2015 conference, which was held in the United Nations Headquarters in NYC. What a venue!

As well as an update on the OpenStreetMap Carto project I gave a presentation on what I see as some of the development prospects for OSM over the next few years. Making predictions is hard, especially about the future, etc, but I gave it my best shot.

I think it’ll be interesting to look back in a few years and see how much of what I discuss was prescient, and more interestingly, what topics I missed entirely!

One of the sections that interested me most (and took by far the longest to prepare the slides for) is that looking at who our developers are, and how this changes over time. It’s just before the 18 minute mark in the video if you want to have a look.

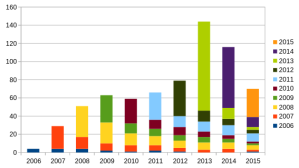

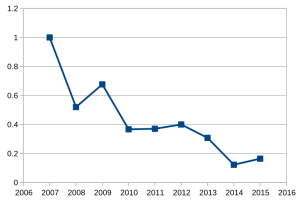

Here’s a couple of the charts, which provide food for thought (bear in mind they were produced in June, so the 2015 numbers reflect only the first 6 months of the year):

I think the future success of OpenStreetMap depends on improving these figures - we should be aiming to retain at least 40% of our developers after their first year of contributing. We’re clearly getting better at attracting new developers, but what do you think is stopping them from sticking around?

This post was posted on 30 October 2015 and tagged OpenStreetMapOpenStreetMap Carto Workshop

At State of the Map Europe I ran a workshop about openstreetmap-carto, the stylesheets that power the Standard map layer on OpenStreetMap.org and many hundreds of other websites. The organisers have published the video of the workshop:

Thanks to the organising team for inviting me to run this workshop - it was certainly well received by the audience, and I spent the rest of the day disussing the project with other developers.

I continue to be surprised by two aspects of openstreetmap-carto. One is how much work is involved in making significant changes to the cartography - after a year and a half, to the casual observer not much has happened! But on the other hand, we now have a large group of people who are commenting on the issues and making pull requests. As of today there are 29 people whose contributions show up in the style, with over 700 issues opened and over 220 pull requests made. Much of the work is now done by Paul Norman and Matthijs Melissen who help review pull requests for me and do almost all of the major refactoring. It's great to have such a good team of people working on this together!

This post was posted on 7 July 2014 and tagged OpenStreetMapA sneak peak at Thunderforest Lightning maps

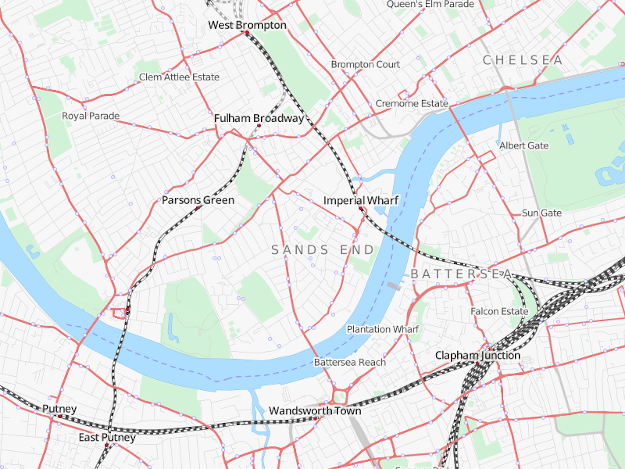

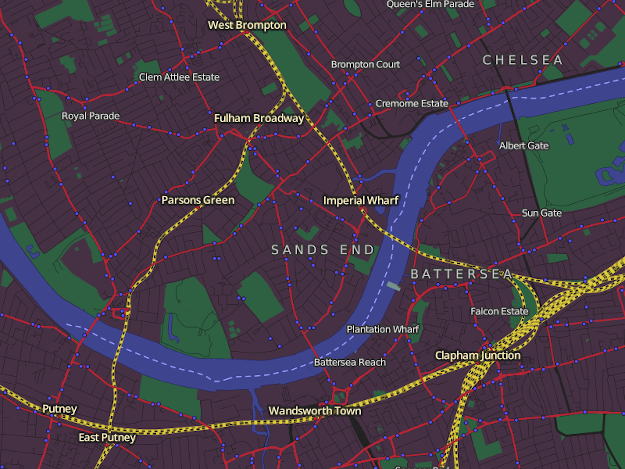

Here’s a few screenshots from my new Lightning tile-server:

A refresh of the Transport Style, built on a brand new, state-of-the-art vector tiles backend.

Thunderforest Lightning makes it easy to create custom map styles sharing vector tile backends. Here’s a Dark variant for the Transport layer.

Vector tiles bring lots of other benefits - like high-performance retina maps!

Development is going full-steam, and Lightning will be launching soon. Check back for more updates!

This post was posted on 28 March 2014 and tagged mapnik, OpenStreetMap, thunderforest, vectorTending the OpenStreetMap Garden

Yesterday I was investigating the OpenStreetMap elevation tag, when I was surprised to find that the third most common value is '0.00000000000'! Now I have my suspicions about any value below ten, but here are 13,832 features in OpenStreetMap that have their elevation mapped to within 10 picometres - roughly one sixth of the diameter of a helium atom - of sea level. Seems unlikely, to be blunt.

It could of course be hundreds of hyper-accurate volunteer mappers, but I immediately suspect an import. Given the spurious accuracy and the tendancy to cluster around sea level, I also suspect it's a broken import where these picometre-accurate readings are more likely to mean "we don't know" than "exactly at sea level". Curious, I spent a few minutes using the overpass API and found an example - Almonesson Lake. The NHD prefix on the tags suggests it came from the National Hydrography Dataset and so, as supected, not real people with ultra-accurate micrometres.

But what concerns me most is when I had a quick look at the data layer for that lake - it turns out that there are three separate and overlapping lakes! We have the NHD import from June 2011. We have an "ArcGIS Exporter lake" from October that year, both of which simply ignore the original lake created way back in Feb 2009, almost 5 years ago. There's no point in having 3 slightly different lakes, and if anyone were to try to fix a misspelling, add an attribute or tweak the outline they would have an unexpectedly difficult task. There is, sadly, a continual stream of imports that are often poorly executed and, worse, rarely revisted and fixed, and this is just one case among many.

Mistakes are made, of course, but it's clear that data problems like these aren't being noticed and/or fixed in a reasonable timescale - even just this one small example throws up a score of problems that all need to be addressed. Most of my own editing is now focussed on tending and fixing the data that we already have, rather than adding new information from surveys. And as the size of the OpenStreetMap dataset increases, along with the seemingly perpetual and often troublesome importing of huge numbers of features, OpenStreetMap will need to adjust to the increasing priority for such data-gardening.

This post was posted on 10 December 2013 and tagged imports, OpenStreetMapNew OpenStreetMap Promotional Leaflets

They’re here!

If you want some to give out to potential new mapper recruits, you can order the OpenStreetMap leaflets and I’ll post them to you.

This post was posted on 23 October 2013 and tagged OpenStreetMapUsing Vagrant to test Chef cookbooks

I’ve previously discussed using Chef as a great way to manage servers, the key part of the process being writing “cookbooks” to describe what software you want installed, how it should be configured, and what services should be running. But a question that I’ve been asked by a few people is how do I test my cookbooks as I are writing them?

Of course, a simple way to test them is run them on my laptop - which would be great, except that I would end up with all kinds of things installed that I don’t need, and there’s things that I don’t want to repeatedly uninstall just to check my cookbooks install it properly. The second approach is to keep run and re-run them on a server as I go along, but that involves uploading a half-written cookbook to my chef server, running chef-client on the server, seeing if it worked, rinsing and repeating. And I’d have to be brave or foolhardy to do this when the server is in production!

Step forward Vagrant. Vagrant bills itself as a way to:

“Create and configure lightweight, reproducible, and portable development environments.”

but ignore the slogan, that’s not what I use it for. Instead, I treat Vagrant as:

“A command-line interface to test chef cookbooks using virtual machines”

After a few weeks of using chef, I’d started testing cookbooks using VirtualBox to avoid trashing my laptop. But clicking around in the GUI, installing VMs by hand, and running Chef was getting a bit tedious, never mind soaking up disk-space with lots of virtual machine images that I was loathe to delete. With Vagrant, however, things become much more straightforward.

Vagrant creates virtual machines using a simple config file, and lets you specify a local path to your cookbooks, and which recipes you want to run. An example config file looks like:

Vagrant.configure("2") do |config|

config.vm.box = "precise64"

config.vm.provision :chef_solo do |chef|

chef.cookbooks_path = "/home/andy/src/toolkit-chef/cookbooks"

chef.add_recipe("toolkit")

end

config.vm.network :forwarded_port, guest: 80, host: 11180

end

You then run vagrant up and it will create the virtual machine from the “precise64” base box, set up networking, shared folders and any other customisations, and run your cookbooks. If, inevitably, your in-development cookbook has a mistake, you can fix it and run vagrant provision to re-run Chef. No need to upload cookbooks anywhere or copy them around, and it keeps your development safely separated from your production machines. Other useful commands are vagrant ssh to log into the virtual machine (if you need to poke around to figure out if the recipes are doing what you want), vagrant halt to shut down the VM when you’re done for the day, and finally vagrant destroy to remove the virtual machine entirely. I do this fairly regularly - I’ve got half a dozen Vagrant instances configured for different projects and so often need to free up the disk space - but given I keep the config files then recreating the virtual machine a few months later is no more complex than vagrant up and a few minutes wait.

Going back to the original purpose of Vagrant, it’s based around redistributing “boxes” i.e. virtual machines configured in a particular way. I’ve never needed to redistribute a box, but once or twice found myself needing a particular base box that’s not available on vagrantbox.es - for example, testing cookbooks on old versions of Ubuntu. Given my dislike of creating virtual machines manually, I found the Veewee project useful. It takes a config file and installs the OS for you (effectively pressing the keyboard on your behalf during the install) and creates a reusable Vagrant base box. The final piece of the jigsaw is then writing the Veewee config files - step forward Bento, which is a pre-written collection of them. Using all these, you can start with a standard Ubuntu .iso file, convert that into a base box with Veewee, and use that base box in as many Vagrant projects as you like.

Finally, I’ve also used Vagrant purely as a command line for VirtualBox - if I’m messing around with a weekend project and don’t want to mess up my laptop installing random dependencies, I instead create a minimal Vagrantfile using vagrant init, vagrant up, vagrant ssh, and mess around in the virtual machine - it’s much quicker than installing a fresh VM by hand, and useful even if you aren’t using Chef.

Do you have your own way of testing Chef cookbooks? Or any other tricks or useful projects? If so, let me know!

This post was posted on 13 September 2013 and tagged chefGetting Started With Chef

A little over a year ago I was plugging through setting up another OpenCycleMap server. I knew what needed installing, and I'd done it many times before, but I suspected that there was a better way than having a terminal open in one screen and my trusty installation notes in the other.

Previously I'd taken a copy of my notes, and tried reworking them into something resembling an automated installation script. I got it to the point where I could work through my notes line-by-line, pasting most of them into the terminal and checking the output, with the occasional note requiring actual typing (typically when I was editing configuration files). But to transform the notes into a robust hands-off script would have been a huge amount of work - probably involving far too many calls to sed and grep - and making everything work when it's re-run or when I change the script a bit would be hard. I suspected that I would be re-inventing a wheel - but I didn't know which wheel!

The first thing was to figure out some jargon - what's the name of this particular wheel? Turns out that it's known as "configuration management". The main principle is to write code to describe the server setup, rather than running commands. That twigged with me straight away - every time I was adding more software to the OpenCycleMap servers I had this sinking feeling that I'd need to type the same stuff in over and over on different servers - I'd prefer to write some code once, and run that code over and over instead. The code also needs to be idempotent - i.e. it doesn't matter how many times you run the code, the end result is the same. That's about the sum of what configuration management entails.

There's a few open-source options for configuration management, but one in particular caught my eye. Opscode's Chef is ruby-based, which works for me since I do a fair amount of ruby development and it's a language that I enjoy working with. And chef is also what the OpenStreetMap sysadmins use to configure their servers, so having people around who use the same system would simply be a bonus.

What started off as a few days effort turned into a massive multi-week project as I learned chef for the first time, and plugged through creating cookbooks for all the components of my server. It was a massive task and took much longer than I'd initially expected, but 18 months on it was clearly worth it - I'd have never been able to run enough servers for all the styles I have now, nor been able to keep up with the upgrades to the software and hardware without it. It's awesome.

So here's some tips, for those who have their own servers and are in a similar position to what I was.

I'll be writing more about developing and testing cookbooks in the future - it's a whole subject in itself!

This post was posted on 19 November 2012 and tagged chef, opencyclemapsubscribe via RSS